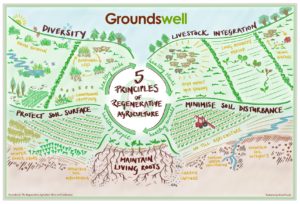

5 Principles of Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative Agriculture is quite simple: it is any form of farming, ie the production of food or fibre, which at the same time improves the environment. This primarily means regenerating the soil. It’s a direction of travel, not an absolute.

For millennia, farmers have taken healthy soils and ploughed them and planted into the clean, exposed surface. For some years, their crops would grow well as there would be little competition from weeds and there would be plenty of freely available nutrients, but after a few years of this, the soil would lose health; crop yields would plummet so that the farmers were forced to rest and/or feed their land. The ancient Romans and good farmers ever since have had to do this but nonetheless, over time, poor farming has resulted in soils becoming so unhealthy that they’ve eventually been blown or washed away: the Land of Milk and Honey that Moses led his people to, or the North African bread basket that fed the Roman Empire are both now deserts. The dust-storms in the last hundred years in America show this is still going on.

A healthy soil is a fabulously complex ecosystem, comprising countless billions of microscopic organisms all working away in their own little niches, feasting on each other and sugars exuded from the roots of growing plants. The whole system is ultimately fuelled by growing plants, whilst at the same time the system helps the plants grow.

We’ve all got so used to our soils being as they are, that it is hard to imagine how much better they could be. I suspect that there isn’t any soil in this part of the world that couldn’t be improved in some way so there is scope for every acre in the country to be regenerated. Compare a spadeful of soil from an arable field to the soil under some permanent pasture on the other side of the hedge, or if you don’t have permanent pasture, then compare with the undisturbed ground under the hedge.There you’ll see lovely dark, crumbly, sweet smelling soil, crawling with worms and life. That’s what your arable land could be like.

In the past we accepted that soils got worse as we farmed. Now we know that they don’t have to. If we mimic a permanent pasture whilst growing annual crops, we can start to reverse the degradation. This gives us five principles to follow:

1. Don’t disturb the soil.

Soil supports a complex network of worm-holes, fungal hyphae and a labyrinth of microscopic air pockets surrounded by aggregates of soil particles. Disturbing this, by ploughing or heavy doses of fertiliser or sprays will set the system back.

2. Keep the soil surface covered.

The impact of rain drops or burning rays of sun or frost can all harm the soil. A duvet of growing crops, or stubble residues, will protect it.

3. Keep living roots in the soil.

In an arable rotation there will be times when this is hard to do but living roots in the soil are vital for feeding the creatures at the base of the soil food web; the bacteria and fungi that provide food for the protozoa, arthropods and higher creatures further up the chain. They also keep mycorrhizal fungi alive and thriving and these symbionts are vital for nourishing most plants and will thus provide a free fertilising and watering service for crops.

4. Grow a diverse range of crops.

Ideally at the same time, like in a meadow. Monocultures do not happen in nature and our soil creatures thrive on variety. Companion cropping (two crops are grown at once and separated after harvest) can be successful. Cover cropping, (growing a crop which is not taken to harvest but helps protect and feed the soil) will also have the happy effect of capturing sunlight and feeding that energy to the subterranean world, at a time when traditionally the land would have been bare.

5. Bring grazing animals back to the land.

This is more than a nod to the permanent pasture analogy, it allows arable farmers to rest their land for one, two or more years and then graze multispecies leys. These leys are great in themselves for feeding the soil and when you add the benefit of mob-grazed livestock, it supercharges the impact on the soil.

If you are starting with a permanent pasture, as is nearly 70% of agricultural land in the UK, you might think that you’re already regenerating. However, in the name of improvement, a lot of this land has been ploughed up and reseeded or heavily fertilised and poorly grazed. Instigating a holistically managed grazing regime will transform the soil and the pasture that it grows. A surprising amount of grazing land is actually monocultural, regularly disturbed and is poorly covered. In the wetter and hillier parts of the country this is often enough to cause increased erosion and flooding.

No-one is really sure how good we can make our soils, nay-sayers will tell you, for instance, that there is a limit to how much Carbon soils can sequester. That could be true if soils were only operating in the top six inches, whereas we’ve seen topsoils getting deeper and deeper as time goes on, meaning a greater sponge to hold rainwater and for the roots and fungal mycelium to operate in, and making ever more room for safe long-term Carbon storage. Regenerative farming isn’t just good for farmers, it is really the only way, if performed across the globe, that humanity can have any hope of living on a pleasant planet.

John Cherry, Groundswell Host Farmer

Read Professor Karl Ritz’s summary of the Five Principles here.

Find out more about Groundswell